Win Lose Or Draw Phrases

In the first-ever season of Sesame Street, in 1970, cast member Bob McGrath appeared in a memorable sketch where he receives a delivery from his local grocer, a grumpy blue muppet. "Did you get everything I ordered?" McGrath asks. "No," comes the reply, but he's helpfully supplemented the delivery with other fresh veggies. McGrath breaks into song, a version of the now iconic "People in Your Neighborhood," to explain to kids the role a grocer plays in the community. The grocer is the bearer of sustenance.

A few weeks ago, during Super Bowl LV, "People in Your Neighborhood" got remixed into an anthem for the app-based delivery platform DoorDash to signal to the world that it is expanding from restaurants to convenience and grocery. In a crisp 60 seconds, a tap dancing Daveed Diggs (Hamilton)—directed by French auteur Michel Gondry (Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind)—wanders through a hyperrealized Sesame Street urbanscape with Big Bird, Elmo, and Super Grover, pointing out all the great local businesses. His message: Your neighborhood is a bounty of bakeries, grocery stores, restaurants, and smoothie stalls. And in 2021, DoorDash is the bearer of sustenance.

For DoorDash, its Super Bowl bet paid off. It informed tens of millions of viewers that DoorDash could bring them everything from both "big shops and mom and pops," as Diggs crooned. It told investors that the company had a strategic plan to live up to and grow into its lofty valuation. Finally, it put a happy face on what's a highly challenging, cutthroat business which has yet to produce a successful company built to last. The ad may have cost somewhere north of $10 million to produce and air, including a $1 million donation to Sesame Workshop, but DoorDash's market cap increased by $10 billion, to more than $65 billion, in the 10 days after the ad debuted.

For almost all of DoorDash's seven-plus years, two things about the company have been true: It has aspired to be a logistics company that did more than restaurant delivery—one of the first articles ever written about the startup, in March 2014, was headlined 'DoorDash enters food-delivery fray with much grander ambitions'—and it's been controversial as it's pursued those dreams. It has been accused of "swiping" delivery driver tips, and restaurants have sued it for listing their eateries on its platform without their consent. DoorDash has also fielded complaints from the restaurants it aims to serve for taking too fat a slice of their revenues. Finally, it took part in a $200 million-plus campaign last year to convince Californians to legalize the use of contract labor in delivery, via ballot Proposition 22, thereby preventing workers from attaining the protections that come with employee status.

So when DoorDash went public just over two months ago and stock-market investors bid the company's shares up to 92% higher than its IPO price on its first day, the fervor, which valued the company almost four-times higher than its last private fundraising in June 2020, only further stoked the debate around DoorDash. How could a company with just one quarter of profitability—$23 million in the second quarter of 2020 amid a pandemic that forced most people to stay home and avoid dining out—be valued at almost twice that of, say, Chipotle? Does DoorDash even have a path to profitability? Food delivery is a notoriously bad business, littered with corpses: Kozmo, Sprig, Maple, Ando, Munchery, to name the highest-profile failures. Even Amazon—the company DoorDash would most like to emulate—shuttered its restaurant delivery service.

When I ask DoorDash CEO Tony Xu what he believes that no one else believes, he replies, "that my business works." He's joking, but the wisecrack reveals the struggle he's endured to convince investors and the media that DoorDash has a viable business model. That one quarter of profit came during a time when DoorDash had slashed its commission rates in half for small restaurants coping with the pandemic. But it was also the same time frame that it started selling convenience items, and data from the analytics firm Second Measure reveals that 56% of DoorDash's customers used them exclusively for delivery, an indication that it is securing loyal customers. When customers stick around beyond a year, DoorDash says they contribute to the company's profit. Customer loyalty and the company's scale have attracted big businesses, both to its marketplace and its white-label delivery service.

DoorDash believes that as people continue to struggle with balancing work and the rest of their lives—from child rearing to carving out time for themselves—its path to profitability lies in soothing the anxieties of middle-class customers who don't have the time or energy to make dinner or go shopping. The end of the pandemic may dampen Americans' appetite for delivery. But if it doesn't, what do we lose when we value convenience at all costs?

"We make a small amount of money on a lot of activities," says Xu, dressed in Silicon Valley's most iconic fashion pairing, a Patagonia demi-zip fleece and rectangular black glasses, when he and I chat via Zoom in early February. "Our business is maniacally working down costs every single day, by making sure that there are no defects so customers can have that perfect order."

Although consumers perceive DoorDash as a useful phone app for ordering restaurant delivery, it actually does much more than that. It builds websites for restaurants through an offering called Storefront. It also has a white-label service called Drive that gives restaurants like Chipotle access to an on-demand delivery workforce without the DoorDash branding.

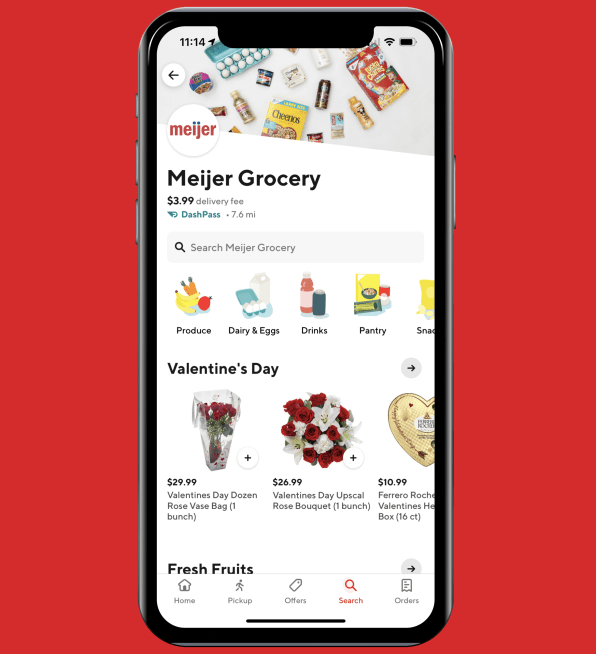

As the company pursues its ambitions beyond food and expands into grocery, drugstore, pet supplies, and convenience items, it's building a network of vendor relationships with such major grocers and big-box stores as CVS, Walgreens, Albertsons, Safeway, Meijer, Hy-Vee, Walmart and Sam's Club, Petco and PetSmart. It has amassed 21,000 convenience stores on its platform. DoorDash has also grown its Drive offering to include such retailers as Walmart and Bloomingdale's, so customers who lived near one of its department stores, for example, could have ordered a Valentine's Day gift as late as noon on February 14 and had it delivered on the holiday by a Dasher. (DoorDash doesn't currently break out revenues from its different business verticals.)

These additional commercial offerings operate on the same model as DoorDash's restaurant business: The company charges retailers a commission on sales based on the services they use in addition to delivery and processing fees. Restaurateurs have shown commissions to be in the realm of 30% of sales. (DoorDash declined to disclose its fee structure.) It's a low-margin business that requires huge scale to eke out a profit and DoorDash mostly relies on non-exclusive relationships, so it has to win on consumer loyalty. It does this by growing the variety of goods on offer in its marketplace and focusing on user experience. "What we find is that once a customer goes beyond food and they realize that they can get the entire breadth of the convenience store delivered to them in 20, 30 minutes, it's a game changer," says DoorDash COO Christopher Payne, who worked for Amazon in the late 1990s where he was responsible for the bookseller's move into video, electronics, and computer software.

Last August, DoorDash introduced DashMart, virtual convenience stores that it operates in 25 cities. DashMarts sell everything from toilet paper to local specialties. (In Chicago, for example, it has sauces from the renowned restaurant Girl and the Goat.) Xu says that he wants to provide products that consumers might not be able to get from other convenience stores. He also says that he's willing to stock house-brand products from any of DoorDash's merchants, and those merchant partners are cool with competing on the DoorDash marketplace. "We're well aware that DoorDash has their DashMart offering and has other retailers that they partner with as well," says Stefanie Kruse Curley, general manager of digital commerce at Walgreens. So far, she says, the competition hasn't impacted sales.

There are some signals that DoorDash's pursuit of low-margin services is working. According to an analysis of the company's IPO prospectus by Alex Taussig, a general partner at the venture-capital firm Lightspeed (which was not a DoorDash investor), the company is recouping its marketing spend to acquire customers within 12 to 18 months and is generating three to four times that expense in the first three years. When I interviewed Xu in 2018, just after his company raised $535 million in a round led by SoftBank, he told me the company was already profitable in its earliest markets, and "our newer markets are getting to those milestones faster than our older markets did," he said.

Additionally, DoorDash appears to be winning market share that could turn into profitable customers within the next few years. In January, the analytics firm Edison Trends released fortuitously timed metrics (given DoorDash's forthcoming push beyond restaurants) revealing that it leads the market in convenience store delivery, carrying 60% of those packages. Around the same time, another commerce analytics firm, Second Measure, showed DoorDash owned a little more than half of the overall delivery market and that it has the most loyal customer base—thanks in part to its 5 million subscribers to DashPass, its subscription rewards program—though the report also noted there are fewer loyal customers than ever among delivery services.

"I've always thought about DoorDash . . . as a system that serves a city," Xu tells me. "If we can make the city successful, we're going to be successful." What does it mean to serve a city? Xu likes to talk about DoorDash in terms of contributing to a city's gross domestic product (GDP), the economic indicator used to measure the relative health of an economy. In recent years, though, GDP has faced significant criticism for its myopic focus on growth while not accounting for its less savory effects. Worldwide, GDP has increased in parallel with rising income inequality, hunger, poverty, and job insecurity.

To deliver Xu's promise of giving consumers "the best of your city," as he says, DoorDash needs to woo a wide variety of restaurants and retailers. Many have come to DoorDash because of its scale and success in the suburbs. Some also see the change to California's labor laws as a sign of the service's potential longevity. In early January, Albertsons, which operates 2,200 supermarkets in 34 states, opted to "discontinue using our own home delivery fleet across a variety of market areas and states," as it shared in a statement at the time.

The grocer had already been using DoorDash Drive since 2019, and now some of those full-time jobs from its own fleet would be outsourced to DoorDash.

Back in 2014, when DoorDash had just graduated from its origins as a Stanford Business School project called Palo Alto Delivery, an entrepreneur named Adam Price was in New York building out a similar idea. His company, Homer, had developed software that made local logistics more efficient and cheaper than traditional courier businesses. He quickly managed to attract the kind of fast-casual chain restaurants—Chopt, Dig Inn, and Dos Toros—that millennials, who were already using their phones to run the fine details of their lives, were queueing around the block for.

The difference between Price and his would-be West Coast rivals? Price decided to hire his delivery workers as employees.

Full-time or part-time, all were guaranteed a set of protections: minimum wage, health insurance, overtime pay, unemployment, workers compensation, and tax contributions. "I thought it was just a matter of time before contractors change to employees," he says, recalling his belief that regulators would crack down on gig companies' worker classification infractions.

Lawmakers, though, did not meaningfully step in. Contract labor had long been on the rise, and in the wake of the 2008 recession, underemployment remained high and wage growth low. Meanwhile, venture capital was flowing freely into gig companies and plenty of people were willing to work for the wages on offer. President Barack Obama hailed the gig economy as the future, saying in 2015, "We've got folks who are getting a paycheck driving for Uber or Lyft; people who are cleaning other people's houses through Handy; offering their skills on TaskRabbit. And so there's flexibility and autonomy and opportunity for workers."

In 2019, the same year that an Internal Revenue Service study found that the segment of workers collecting income as independent contractors has risen 22% since 2001, California legislators sought to push against the tide with the passage of a law known as Assembly Bill 5 (AB5). It aimed to more clearly define the distinction between gig workers and employees. Contractors are supposed to be free to pick up or refuse whatever job they want and do it in the manner they see fit. If a company is controlling too many aspects of a contractor's work, then they are likely a misclassified employee. DoorDash controls how fast food needs to be delivered and requires workers to maintain high customer ratings. But workers are also free to decline jobs and work for other gig platforms.

DoorDash exerts just enough control to maintain a consistent, timely delivery experience and in turn keep customers coming back. "There's not one thing that a customer's going to grade you on," says Xu. "They're going to grade you on: What can I get delivered? How does it show up? How much did it cost? And especially if things went wrong, what did they do to take care of me?" DoorDash, alongside other app-based platforms that rely on gig labor such as Uber, Lyft, and Instacart, mounted a record $200 million campaign in support of the proposition they got on the California ballot in 2020. DoorDash contributed $48 million to the effort.

Prop 22's passage cemented gig workers' status as independent contractors in the state. But it also committed platforms to a new set of obligations to workers, including earnings minimums and occupational accident and vehicle insurance—but only when the worker is actively engaged on a job, not before or after. While these are gains for contract delivery workers, who previously had no legal entitlements, Prop 22 does not offer the same breadth of protections as those tied to employee status (DoorDash says it provided occupational accident insurance prior to Prop 22). "Tech has found a way to basically outmaneuver legislation that took a hundred years to build," says Price, alluding to such laws as the 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act. In 2019, Price sold Homer to Waitr, and converted to gig labor. DoorDash and its fellow gig companies are now expected to seek to extend Prop 22 nationwide.

The win set DoorDash up to go public five weeks after the vote, because it ameliorated investors' concerns about the company's labor costs. It also offered hope that the company might be able to put a rash of legal challenges behind it. Last October, DoorDash settled class-action suits against it for worker misclassification in California, dating back to 2016, and Massachusetts, dating back to 2014. The price: $89 million. In its IPO prospectus, it also acknowledged that more than 35,000 delivery workers have filed or intend to file arbitration claims relating to worker misclassification. "We anticipate that the aggregate amount of payments to Dashers and Caviar delivery providers under these individual settlement agreements, including attorneys' fees, will be approximately $85 million." DoorDash has also gotten in trouble for, as the attorney general of Washington, D.C., put it, using "consumer tips to offset the company's payment to workers," a practice the company changed in August 2019. There are still several outstanding lawsuits alleging fraud and unjust enrichment, and the company expects additional claims. DoorDash reported a $131 million loss for the first nine months of 2020, so legalizing its labor model could significantly reduce legal costs and help swing the company to profitability.

Xu maintains that his platform is for supplemental income only and says that for 91% of Dashers, DoorDash is a pocket-change gig. The vast majority of Dashers work less than 10 hours a week, according to DoorDash data. Through Prop 22, Xu says, he was hoping to standardize and attach protections to a more flexible format of work. "We're trying to work with everyone involved, starting with the Dashers and certainly with others—whether it's elected officials, regulators, legislators, whoever's willing to listen—to design a system that is actually going to work for the hundreds of millions of workers out there, because it doesn't fit any conventional standard of work." On Thursday, February 25, the company offered an update on the early impact of Prop 22, publishing that Bay Area Dashers are earning "over $36 an hour while on deliveries" while Sacramento Dashers are making "over $32 while on deliveries."

Outside estimates, though, suggest much lower average earnings than DoorDash's rosy numbers. In January 2020, Working Washington showed that when accounting for expenses like additional payroll taxes and cost of mileage, average earnings on DoorDash were about $1.45 per hour. "Nearly a third of jobs actually pay less than $0 after accounting for these basic expenses," the labor rights organization said. These figures are for workers outside of Prop 22's jurisdiction, so are not directly comparable, but they do examine how costs can add up for drivers. However, their estimated gross wage was roughly in line with DoorDash's at the time ($15.76 versus $18.54). DoorDash says it national average gross wage is now $22 per active hour.

Most gig workers do want the flexibility that Xu says they want, and not all of them want to become employees (a significant chunk voted in favor of Prop 22). However, they may want more protections than they currently have access to, such as better wage transparency, access to bathrooms while working (which DoorDash say it's working on with restaurants), and limits on delivery weight and distance, especially for those traveling by bicycle. Prop 22 doesn't account for these specific worker issues or have a means to resolve any others that will inevitably arise over time. Amending—or overturning—Prop 22 will require a seven-eighths super majority of both houses of the California legislature. It does not give Dashers the right to unionize and therefore advocate for themselves collectively. DoorDash has launched a community council for its Dashers, but that is not an independent entity.

"Nobody is operating on the worker's behalf, and everybody is claiming to operate on the workers behalf," says Marshall Steinbaum, an economist and antitrust expert at the University of Utah who would like to see federal amendments to antitrust laws that make it easier to resolve these classification issues. "I hope there's ground for optimism, but I'm not sure that there is."

When the pandemic hit, Phillip Foss, owner of the Chicago restaurant EL Ideas, turned his Michelin-starred elevated dining experience into a barbecue takeout joint.

He ran the numbers on using a delivery service for Boxcar BBQ. Most entrees, such as the half chicken, half rack of ribs, and sloppy joe, are $19, and Chicago, like several other cities, has instituted a 15% cap on commissions, which is around half of what he might typically pay a delivery service like DoorDash. But he determined that if he signed up it would cut too deeply into his margins, so he did not engage a delivery service. Foss is the only person working at Boxcar. There is no culinary team. No dishwashing crew. "Justifying giving more money to pretty much everybody involved in it but me had a bad flavor," he says.

In normal times, amid the haze of alcohol sales and big dining checks from nine-course tasting menus, delivery fees might not seem so bad. "Your instinct is to sell," says Foss. "You'll do anything reasonable and unreasonable sometimes to sell your product." Once a restaurant commits to working with a delivery app, though, it's hard to get off, Foss says. Customers now expect to order your food inside these apps, he explains, and you alienate them by taking it away. There is also an incredible number of potential new customers on those apps.

DoorDash says that its fees cover a range of services that help businesses grow their customer base. It also notes that according to an internal analysis the odds of staying in business was eight times better for restaurants on its platform compared to all U.S. restaurants. But Foss is not the only independent restaurateur who's done this calculus and is embracing alternatives. They're urging customers to take a walk around the neighborhood and pick up their orders. Some are using cheaper alternative platforms like ChowNow, which offers online ordering for people picking up. Foss is also interested in the idea of a co-op delivery service that multiple restaurants would buy into.

"I'm so deep in over my head just trying to keep business afloat," says Foss, "[DoorDash and Uber are] running advertisements in the Super Bowl! Look at how much they're spending on their marketing while the very industry that keeps their wheels going is crumbling." In it owns assessment of its impact on the economy, DoorDash found that its platform generated $13.2 billion in economic activity in 2019, roughly half of which wouldn't have existed otherwise.

Both DoorDash and Uber Eats emphasize the local nature of their services in their ads, and the word "local" appears 300 times in DoorDash's IPO prospectus. But "local" means something very specific within the zeitgeist. It evokes images of mom-and-pop shops with striped awnings overhead and wooden shelves. "Local" is also a mantra among the environmentally minded, who shop local to lower their carbon footprint.

The reality, though, is that shopping "local" is not so quaint. For many locales, Walmart and Applebees may be your choices, and the goods are likely to come by car, not zero-emissions bicycles.

"Small businesses, medium-sized businesses, and large businesses. That's what we mean by local businesses," says Xu, an inclusive rainbow-striped DoorDash symbol hanging overhead in his Zoom window.

If smaller restaurants stop using DoorDash, corporate chains may well replace them, as well as national convenience and grocery brands that compete with Amazon and have budgets devoted to their "omni-channel strategy." These companies see DoorDash's fees as a mere cost of doing business. "These customers are incremental," says Alex Augugliaro, manager of delivery services at Wawa, the cult-favorite convenience-store chain in the mid-Atlantic region that's a vendor on DoorDash. "They have to be profitable, but they don't have to be as profitable."

Although DoorDash may well be able to build a low-margin, profitable enterprise serving these businesses, that is not why the company is valued at $65 billion. The trick to earning that growth expectation is not just a matter of maniacally shaving costs, as Xu said, but selling more directly to consumers. DoorDash will continue to build out its local logistics network with partners like Wawa, but the company's future feels like it's in DashMart, its virtual convenience store. "It's bringing selection where it doesn't exist," Xu says.

DoorDash is also extending that vertical integration by getting into the ghost kitchen business. Ghost kitchens—also sometimes referred to as cloud kitchens—are commercial facilities that have been optimized to pump out food for delivery. They're located wherever rents are cheapest and typically host multiple companies, further reducing overhead. Estimates of how many ghost kitchens there are vary widely, but conservatively, experts suggest there are at least 2,000 of them. Ghost kitchens reject the beautiful, wonderfully inefficient experience of restaurant dining. They're also a bit of a misnomer. The phrase, ghost kitchen, suggests a spirit without a body to call home, but really it's quite the opposite: a vessel without a soul.

DoorDash already operates a ghost kitchen in Redwood City, California, in which a mix of local and national chains operate: Italian Homemade, Rooster & Rice, The Halal Guys, Humphry Slocombe, and Chick-fil-A. In December, the YouTube star MrBeast generated a stir when he instantly launched a national 300-location burger chain using the ghost-kitchen operator Virtual Dining Concepts, with delivery provided by DoorDash.

To the customer scrolling through the DoorDash app, there is no difference between a virtual restaurant like MrBeast Burger and the real one down the street. While DoorDash is working with both independent restaurants and national brands in its first ghost kitchen, the excitement for this concept is in being able to tailor menus and branding to whatever people are actively looking to eat. Just as DoorDash is doing in convenience with DashMart, using its proprietary data to give customers what they say they want.

DoorDash is exploring other measures to boost profitability. The company has dabbled in automated food delivery with sidewalk robots since 2017 and self-driving cars, which could cut labor costs further. It also acquired Chowbotics, a salad-tossing bot that can also assemble any number of "bowls," and plans to license it out to restaurants.

While replacing workers with robots is a long-shot bet, these moves do chip away at DoorDash's promises regarding both small businesses and its gig-based workforce. The company's push into automation and virtualization only further creates a simulacrum of neighborhood businesses in its Marketplace rather than a direct reflection of what's actually on Main Street.

Which brings us back to DoorDash's Michel Gondry-directed Super Bowl commercial. Watch it again and you'll notice that there is a stunning lack of delivery people. A Dasher whizzes by in the first second of the ad, but their face, in profile, is blurred. The camera instead glimpses the tail end of a bicycle affixed with DoorDash's white-symboled red carrier case. Another one can be seen driving by out of focus in the window of a bakery where Cookie Monster is in sharp relief gobbling down chocolate chip treats.

Gondry is known for playing with artifice. Here, the neighborhood is a facsimile, and the puppets are avatars for real people. In his DoorDash daydream, the viewer, you, don't have to think about how the goods come to you—merely that they do.

Win Lose Or Draw Phrases

Source: https://www.fastcompany.com/90607227/doordash-65-billion-valuation-profitability-tony-xu

Posted by: mclaughlinfragend.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Win Lose Or Draw Phrases"

Post a Comment